If you have visited China before, do you remember the excitement and surprises you had?

“Wow, this is the Great Wall!” It is not just one long wall, but rows of steep walls, standing on the mountain ridges and extending to all directions.

“What? This is Alibaba’s headquarter? It’s like a huge campus.” Yes, it has its own post office, gyms, and a huge food court. “Oh, no. I have no Alipay. Do you have cash with you?” Yes, Chinese economy is moving onto a cashless and cardless stage.

These are just some examples of what our Winthrop students felt during their trip to China in May, 2017. Traveling from South Carolina to China is a long and costly journey. Our students, mostly from middle-class and even low-income families, some still teenagers while others seniors, not only witnessed another world civilization which to them only existed in books or on TV in the past, but also observed the power of globalization since the 19th century. In two weeks we traveled to five cities—Shanghai, Suzhou, Hangzhou, Xi’an, and Beijing. We visited the most famous tourist sites, such as the Bund, the Suzhou gardens, West Lake, the Museum of the Terracotta Warriors, the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven, and the Great Wall. We were more than ordinary tourists, however. As we took the Meglev train and high-speed train, we learned about China’s high-speed rail (HSR) network and her HSR diplomacy. We also visited Volkswagen’s Shanghai factory, Alibaba’s headquarter, Chinese Network Television (CNTV), and iQiyi, etc. We learned that Volkswagen has five major campuses in China; the Pakistani prime minister was visiting Alibaba at the same time with us because Alibaba is competing with Amazon for the South Asian e-commerce market; China Central Television (CCTV), the state-operated TV station, valued the power of the internet and established CNTV; and the IP industry boosted the rise of the streaming service—iQiyi, China’s Netflix, as the American Netflix is relying on iQiyi to expand its market share via their cooperation.

Most colleges and universities have study-abroad programs, and China is one of the most common destinations. But what can students obtain from such experiences?

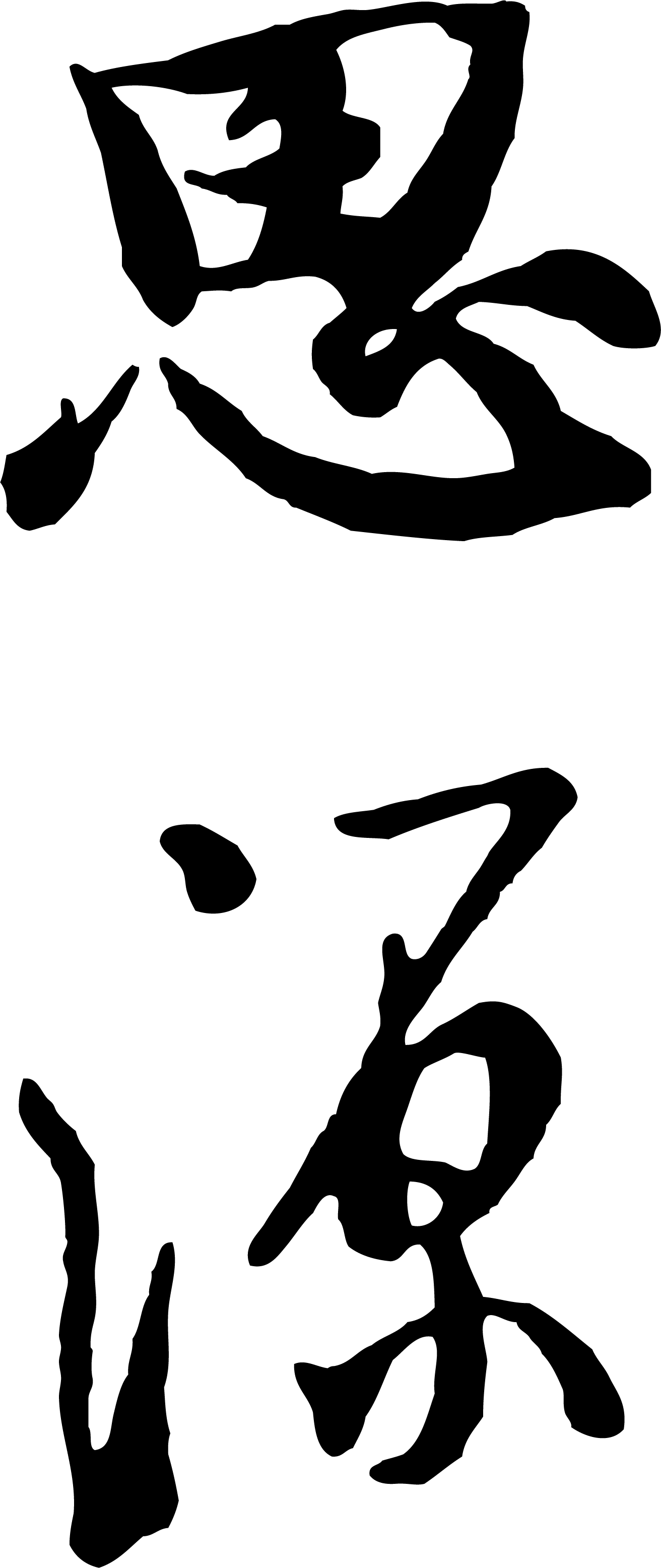

Our theme is to observe how China interweaves traditions and modernity in its national image, and our goal is to give students more global experiences to improve their critical thinking skills and to look beyond symptoms in their life journeys. Students strolled on Nanjing Road to imagine a 1930s Jazz Shanghai. They walked along the Bund at night and photoed Pudong’s neon lights and skyscrapers across the Huangpu River. The famous 101-story Shanghai World Trade Center and the Oriental Pearl Radio & TV Tower are only two of them. When we were boating on West Lake, the whole city of Hangzhou, a city famous for its e-commerce and the Internet service was the background. One day, we witnessed the lively terracotta warriors in Xi’an and wondered how such huge statues were made; the next day we were taking the high-speed train to travel from Xi’an to Beijing in less than five hours.

The students now realize that the distance between South Carolina and China is actually really close because of globalization. As one student said, his friend had thought that there are only two “cities” in China, i.e. Beijing and Shanghai. He replied, “No. There are much more and they are megacities.” In these megacities, a daily challenge was that students had to walk shoulder by shoulder with other tourists and Chinese people. Students had learned about the size of Chinese population—1.38 billion—in opposition to the 322 million population in the US. Nevertheless, they finally experienced it. “This is what it is like with such a huge population in China,” as I told them. Shanghai—24 million; Beijing—22 million; Hangzhou—9.2 million. All mark the challenge that each local government has to face. The same numbers, for them, might suggest all sorts of job opportunities. “On the other hand,” I continued, “there are a lot of fault lines in China. Think about what kinds of political system, economic policy, and society it will and should develop. Think about yourselves and the US. What kinds of opportunities you could have with this population from the US in this age of globalization.”

Students then started to reflect upon their skills and South Carolinian experiences; they reconsider their life and goal after graduation. “What is it truly like in China’s rural area?” “What is the waiter’s average wage?” They raised many questions. We thus discussed the rise of the middle class in China, the real estate bubble, and the infrastructure-building projects and ghost cities. We explored several possible futures that Chinese government, economy, and society will transform to. Many students then told me that they will go back to China soon. The reasons are many, but one is significant—they want to witness the changes. Whatever China is now and will be in the future, students started to shed the old stereotypical images of China and face the true China. China is more than the Forbidden City and the Great Wall. Those are the traditions. Chinese people are no more the “blue ants” that they saw on TV; they are like you and me. But the income inequality and the rural-urban disparities are worsening as the economy grows. These are part of China’s modernity. Why? If China is a black hole, used to be invisible, its shape is getting clearer with this study-abroad experience. Its gravity is too big to ignore, whether or not they like it. And now, this is only the beginning of their lifelong learning journey.